New research estimates the future emissions of potent greenhouse gases based on current trends and compliance with climate policies

By Xinyi Zeng (xinyi.zeng@noaa.gov), Science Communications SpecialistJune 2, 2022

New research published in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics projects future emissions of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), a class of potent greenhouse gasses, based on recent trends and compliance with current policies. The ability to observe trends of these compounds in the atmosphere is made possible by the long-term record of observations produced by the Halocarbons and other Atmospheric Trace Species (HATS) Division within NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory.

As substitutes for ozone-depleting substances, the emissions of HFCs have increased substantially over the past two decades as a response to controls on ozone-depleting substances under the Montreal Protocol. Due to HFCs’ growing climate impact, the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol has scheduled a phase-down of their future production and consumption.

This study is designed to give policymakers quantitative feedback on the future climate benefits anticipated from the Kigali Amendment. The results will guide the Parties to the Montreal Protocol to decide if existing controls in the Protocol need revision, depending on the climate outcomes that they hope to achieve through the Montreal Protocol. Additionally, this study highlights the critical need for continued high-quality, long-term records of atmospheric composition, which NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory has been producing for decades.

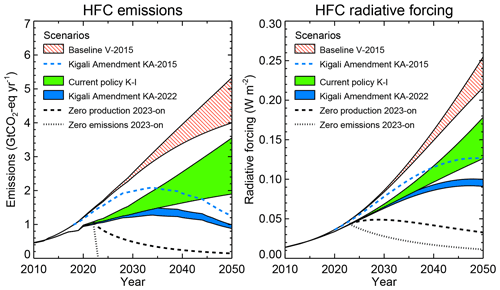

Total CO2 equivalent global HFC emissions derived from NOAA observations continue to increase through 2019, but are about 20% lower than previously projected for 2017-2019, mainly because of the lower global emissions of HFC-143a, which is one of the longer-lived HFCs in use today.

Current Kigali-independent control policies reduce projected emissions in 2050 from 4.0–5.3 GtCO2eq.yr-1 in the absence of controls to 1.9–3.6 GtCO2eq.yr-1, and the added provisions of the Kigali Amendment reduce the projected emissions further to 0.9–1.0 GtCO2eq.yr-1.

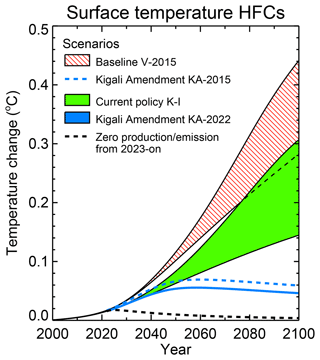

Without any controls, HFC emissions were projected to contribute 0.28-0.44 °C to global surface warming by 2100, compared to a contribution of about 0.04 °C by 2100 with Kigali Amendment controls.

NOAA scientists John S. Daniel at the Chemical Sciences Laboratory, Stephen A. Montzka at the Global Monitoring Laboratory, and CIRES scientist Isaac Vimont at the Global Monitoring Laboratory are co-authors of the paper. NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory provided the HFC measurements used to infer the global total annual emissions from 1990 to 2020. These NOAA measurements are funded in part by NOAA Climate Program Office’s Atmospheric Chemistry, Carbon Cycle, and Climate (AC4) program.

Publication Information

Projections of hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) emissions and the resulting global warming based on recent trends in observed abundances and current policies

Guus J. M. Velders, John S. Daniel (OAR/CSL), Stephen A. Montzka (OAR/GML), Isaac Vimont (OAR/GML & CIRES), Matthew Rigby, Paul B. Krummel, Jens Muhle, Simon O'Doherty, Ronald G. Prinn, Ray F. Weiss, and Dickon Young

The emissions of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) have increased significantly in the past 2 decades, primarily as a result of the phaseout of ozone-depleting substances under the Montreal Protocol and the use of HFCs as their replacements. In 2015, large increases were projected in HFC use and emissions in this century in the absence of regulations, contributing up to 0.5 °C to global surface warming by 2100. In 2019, the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol came into force with the goal of limiting the use of HFCs globally, and currently, regulations to limit the use of HFCs are in effect in several countries. Here, we analyze trends in HFC emissions inferred from observations of atmospheric abundances and compare them with previous projections. Total CO2 eq. inferred HFC emissions continue to increase through 2019 (to about 0.8 GtCO2eq.yr-1) but are about 20 % lower than previously projected for 2017–2019, mainly because of the lower global emissions of HFC-143a. This indicates that HFCs are used much less in industrial and commercial refrigeration (ICR) applications than previously projected. This is supported by data reported by the developed countries and the lower reported consumption of HFC-143a in China. Because this time period preceded the beginning of the Kigali provisions, this reduction cannot be linked directly to the provisions of the Kigali Amendment. However, it could indicate that companies transitioned away from the HFC-143a with its high global warming potential (GWP) for ICR applications in anticipation of national or global mandates. There are two new HFC scenarios developed based (1) on current trends in HFC use and Kigali-independent (K-I) control policies currently existing in several countries and (2) current HFC trends and compliance with the Kigali Amendment (KA-2022). These current policies reduce projected emissions in 2050 from the previously calculated 4.0–5.3 GtCO2eq.yr-1 to 1.9–3.6 GtCO2eq.yr-1. The added provisions of the Kigali Amendment are projected to reduce the emissions further to 0.9–1.0 GtCO2eq.yr-1 in 2050. Without any controls, projections suggest a HFC contribution of 0.28–0.44 °C to global surface warming by 2100, compared to a temperature contribution of 0.14–0.31 °C that is projected considering the national K-I policies current in place. Warming from HFCs is additionally limited by the Kigali Amendment controls to a contribution of about 0.04 °C by 2100.